This blog is in a state of suspended animation

I am much more active on twitter (@mark_haddon) and on instagram (@mjphaddon)

we have a full cast and creative team for polar bears (which opens at the donmar warehouse on 1st april)

http://www.donmarwarehouse.com/pl109cast.html

http://www.donmarwarehouse.com/pl109crew.html

i've been writing an article for the telegraph about the joys of writing drama, not least among which is actually getting out of the house and working with other human beings. rehearsals begin tomorrow...

http://www.libelreform.org/sign

please do sign this petition. it is part of a campaign to change the dangerous and inequitable libel laws in the uk. this is not about intrusion into the lives of celebrities. nor is it simply about right to free speech. it is also about organisations using the sledgehammer of the law to crush critical voices, thereby undermining proper scientific debate. the campaign is supported by the new scientist, the journal of the royal society of medicine, the society of authors and many others (see here for a full list)

in a notorious recent example, the science writer simon singh is being sued by the british chiropractic association for an article in the guardian in which he wrote:

the british chiropractic association claims that their members can help treat childrewith colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections, asthma and prolonged crying, even though there is not a jot of evidence. this organisation is the respectable face of the chiropractic profession and yet it happily promotes bogus treatments.

this seems incontestible to me. they promote these treatments. there is absolutely no evidence for their efficacy. case closed. you'd assume. but simon singh has already spent two years and £100,000 of his own money defending himself, and he and three researchers risk losing £1 million each.

you can read more following the links above, but the mains points are:

(a) english libel laws have been condemned by the un human rights committee.

(b) these laws gag scientists, bloggers and journalists who want to discuss matters of genuine public interest and public health.

(c) our laws give rise to libel tourism, whereby the rich and the powerful come to london to sue writers because english libel laws are so hostile to responsible journalism. (this is why signatories to the petition are encouraged from around the world.)

(d) vested interests can use their resources to bully and intimidate those who seek to question them. the cost of a libel trial in england is 100 times more expensive than the european average and typically runs to over £1 million.

apropos miroslaw balka’s how it is (see tate 1 below) and other works which seek to mimic external environments inside a gallery... it wasn’t until i was travelling home that i remembered james turrell’s deer shelter at the yorkshire sculpture park, a semi-submerged room of concrete seats tilted backwards so that one looks up at a square opening in the roof, the edges of which are so thin you are looking at a square of suspended sky, constantly moving and changing and pouring light down into the room. it’s one of the most simple and sublime and involving works i have ever seen, and deeply moving.

turrell had an exhibition of indoor installations / light sculptures in the park’s gallery several years ago. most were rooms full of vivid, saturated, brightly coloured light, the walls, shadows and sheets of gauze arranged in such a way that you quickly lost a sense of where you were and what you were looking at (i’m not even sure were any sheets of gauze, it was that disconcerting). in short, it did something similar to what balka’s how it is purports to do, but it did it better and with modest means and in a way that seemed both generous and inclusive.

the first proper run since a chaplinesque fall while running over an icy bridge before christmas (legs up, arse down, codeine, hobbling etc.). god, it's good to be properly outside again: the big sky, the flooded river, the space, the quiet, the... well, i don't know the word. and i think not knowing the word is the probably the point. a less grandiose version of wordsworth's presence that disturbs me me with the joy of elevated thoughts... a motion and a spirit that impels all thinking things, all objects of all thoughts, and rolls through all things... except it's more an absence than a presence, more material than spiritual... and trying to articulate the feeling is like staring at the mona lisa through the eyepiece of a camcorder.

halfway through the run it began to snow. fat flakes driving almost horizontally over the meadow like the air had become a huge diagram of wind.

perhaps it's some viking genes somewhere. i'm uncomfortable in the heat, but when the weather gets what other people call bad i'm suddenly at home outside. getting wet, getting dirty, getting cold makes me feel a part of the landscape in a way that a pleasant walk after sunday lunch simply doesn't.

running only increases that sense. indeed i keep remembering a brief passage in richard wrangham's catching fire (see below) where he describes human beings as the running animal, pointing out something i'd never thought of before (because most of us are so sedentary these days), that other animals can run faster over short periods, but we can run for hour after hour if we're fit. and there are very few animals that can do that. so maybe it's not viking genes, maybe it's just human genes.

now i'm just looking forward to more miles and those longer runs upriver where the buildings give way to green.

[photo by pcgn7 @ flickr under creative commons]

[barnett newman's who's afraid of red, yellow and blue, 1966 - not the painting mentioned below, since the tate are not generous when it comes to reproduction rights, though this is partly due to the parsimony of some original copyright holders - certain artists' estates for example - who can be vicious in their pursuit of copyright infringement; some won't even allow their paintings to be glimpsed in the background of phtographs and videos of other works]

while at the tate I spent some time with several abstract expressionist works that I have always loved: barnett newman’s adam and eve, pollock’s summertime: number 9a, franz kline’s meryon... and it struck me for the first time that one of the functions of their size (like most abstract expressionist pictures, these are all big paintings) is to persuade the viewer that they really are art.

i guess context-dependent art began - in the public imagination at least - with marcel duchamps' fountain (1917)

.jpg)

it's hard to think of works of art before this which needed to be displayed reverentially in a gallery or church or other spiritual building for them to be recognised as art. if you found art on a trash-heap you knew it was art.

we have become so used to abstract expressionist paintings being so obviously and unquestionably 'art' (indeed rather earnest and traditional art when compared to the work of these artists' upstart juniors: jasper johns, frank stella, andy warhol...) that we don't notice how easily they could be mistaken for stuff that isn't art. a pollock could be an accident on a studio floor. a barnett newman could be a carpet design. a franz kline could be the first few exuberant strokes of a housepainter starting to cover a wall. banal, maybe, but true. like the urinal they are context-dependent, if not to the same extent. but they solve the problem by being enormous. they carry their own space with them. they overwhelm you. they fill your field of view. they say say look at me and admire.

coincidentally a couple of days later i was watching john logan's play red at the donmar warehouse. it's about mark rothko who, among other things, is grappling with precisely this problem. he is working on his murals for the seagram building in new york, a commission he finally rejects. we don't know precisely why (in real life, at least) but it's fairly clear that however great the power of his paintings to create their own reverential space, they would rapidly have become wallpaper when they were hung above the wealthy, self-satisfied diners in the four seasons restaurant.

[photo by fairlybouyant @ flickr under creative commons]

at the tate yeserday, where i finally saw miroslaw balka's how it is, his installation in the turbine hall, a vast, dark steel container you enter by walking up a ramp then wander around inside. i was disappointed, to be honest. one of the main intentions (i assume he oversaw the accompanying explanatory text) is to profoundly disorient and unsettle the viewer by plunging them into complete darkness, which it does only very briefly. after a matter of seconds you can see the walls (just) and other people and, at any point, you can turn round and see the great rectangle of light where you entered (i actually found it more impressive from the outside, much as i find the millennium wheel more impressive from underneath).

i've read a number of enthusiastic reviews from critics who seem to agree with jonathan jones in the guardian who described the work as terrifying, awe-inspiring and thought-provoking. it embraces you with a velvet chill. which makes me wonder whether he has ever been in the countryside at night. i periodically stay in a part of Herefordshire where there is almost no ambient light at night. when there is cloud cover it is really, really dark. if you wander round outside it's a lot more terrifying, awe-inspiring and thought-provoking than a huge steel container on the south bank. Sometimes it scares the living crap out of me.

how it is kept reminding me of works by the boyle family and mike nelson, artists who recreate in the gallery, with creepy verisimilitude, environments you might find elsewhere. sure it's a surprise to find a pavement on a wall or a huge room filled sand. the change of context makes you think. a bit. but the displaced environment is always reduced in other respects. it's frozen in time. the light is static. the temperature is static. there's no wind, no smell. it's bounded. you can't roll around in it and climb over it and grab handfuls of it.

the world is rich and deep and fascinating. copying bits of it and putting them in a gallery seems rather pointless to me and on the wholeiI prefer artists who add something to the world.

oddly the other work which came to mind when i was walking around in the not-quite-dark was plight by joseph beuys which is - or at least was a few years ago -permanently installed in the centre pompidou: two rooms connected by a low doorway, containing a piano, a table and a thermometer, the walls lagged with thick rolls of heavy felt. beuys doesn't eliminate all sound - just as balka doesn't eliminate all light - but the way in which sounds are so effectively deadened, the way sounds seems to be sucked out of the air is - unlike balka's container - deeply unsettling.

this is doubtless connected to something i had never never really considered before (beuys’ work was more thought-provoking in memory than balka’s was when I was inside it), that we can easily experience the complete absence of light, but despite our regular references to silence, we never experience the complete absence of sound, for even in the quietest places we hear the breath going in and out and the tiny roar of the blood and that faint, high-pitched whine, hardly a noise at all, which sounds as if some nearby electrical object has been left on standby. which i guess it has.

from my inbox this morning:

'dear mr haddon,

we invite you to join 150 of britain's leading thinkers, doers, creators and catalysts for a very special evening in london on wednesday february 10th, 6.30-9.30pm. gathering at a location in central London, you will be joined by conservative leader david cameron presenting his first ever TED talk, an 18-minute idea worth spreading.'

it sounds like the shortest, most boring rave in history (i think i may have stolen that joke from an article in the guardian).

david cameron having a big idea? a big idea being delivered in 18 minutes? an idea worth spreading? i'm not sure whether it's margarine or manure which comes most quickly to mind.

in truth, i find it sad, because i had always harboured a warm feeling about TED ever since i watched dave eggers' inspirational 'once upon a school' presentation in 2008. how ironic that the organisation which provided a platform to help him broadcast this gloriously inclusive idea should become an elitist freemasonry.

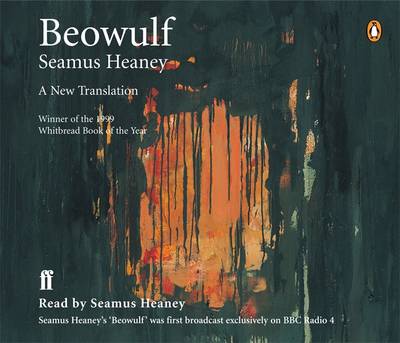

i read this when it came out and it was clearly brilliant, but i'm now listening to it for the first time and i'm coming round to thinking it's a masterpiece, wholly authentic without being in the least antique. i'm struggling to think of any translations of long poems which come close. i keep rewinding and listening to passages because they're almost physically pleasureable.

obviously the poem is - and was - meant to be read aloud. and i could listen to seamus heaney reciting the phonebook to be honest. but i've always found that when a poet reads their work well i'm forced to consume the poetry slowly, at their own speed. consequently i appreciate things which slip under the eye when the book is in front of me (i never realised how good a poet paul farley was, for example, until i heard him read; though he'd recite the phonebook pretty well, too).

one bizarre thing. two words seemed out of place when i was listening to the first part of the poem. anathema and catastrophe, both of which are greek in origin. all the latinate words seem entirely at home alongside their germanic cousins. even gumption (an 18th cy scottish word, apparently, but one which has a jeevesian twenties ring to me) seemed appropriate in context. it must be something, i guess, about greek having always been an alien language in the british isles. though why it would take a 20th cy translation of a 10th cy poem set in denmark to throw the distinction into relief i have no idea...

why is there not a statue of this man on the fourth plinth...? i have just been listening to a backlog of podcasted editions of in our time (the samurai, the geological formation of britain, pythagoras, the silk road, sparta...). time and again a subject which seems unpromising in advance just comes alive. challenging, unpatronising, unashamedly intellectual, a little scruffy at the corners (i alway love hearing the chink of tea cups on the studio table).

the only sad thing is the lack of a full downloadable archive of previous programmes.